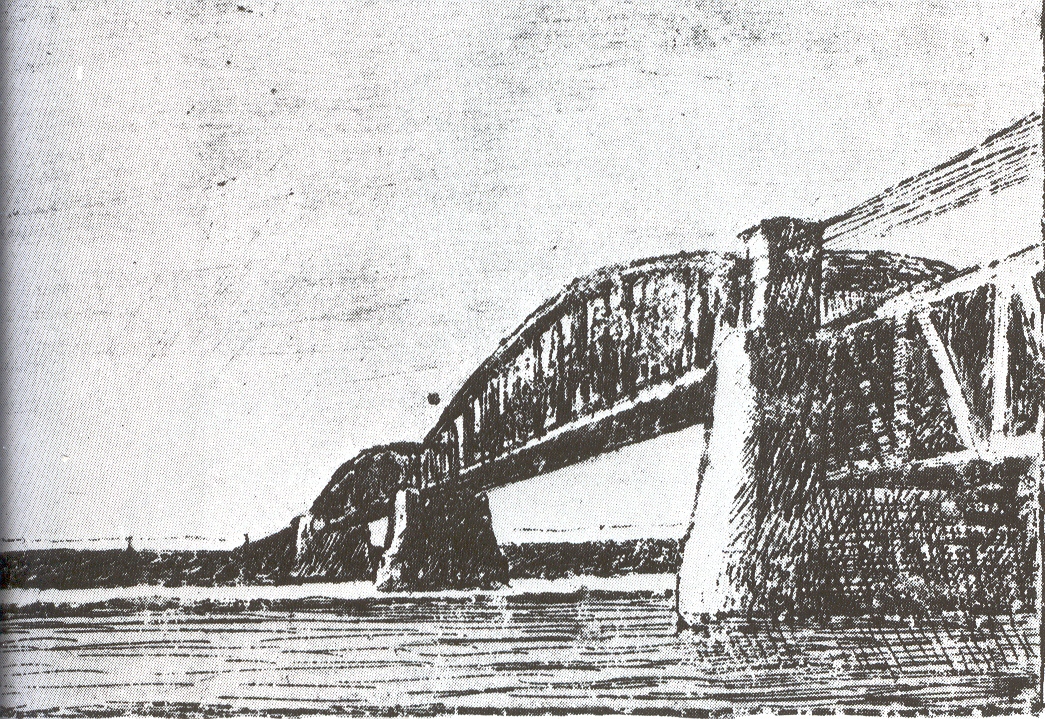

It was a mighty metal construction from 1897: the railway bridge over the Rhine at Oosterbeek. Capturing this bridge was one of the objectives given to the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Parachute Brigade under the leadership of Colonel John Frost during the airborne landings.

They had almost succeeded and it had drastically changed the course of the battle at Arnhem. But as British paratroopers stormed over the bridge, the railway bridge was blown up by the Germans.

Lieutenant Peter Barry, leader of the 9th Platoon of C Company, had been ordered to take the bridge with his men. In Martin Middlebrook’s book on the Battle of Arnhem, Peter Barry’s account of the battle is given:

“While we were taking cover behind an embankment, I saw someone running from the other side of the bridge towards the middle. I saw him bend down to do something. He was dressed in black and had a German army cap on. The distance between us was about 500 meters. I ordered the bren gunner to open fire, but the German ran away without being hit. He had clearly done what he had to do and now escaped.

The company commander then came forward and ordered a section to take the north side of the bridge. That was our side. I went to the bridge with a section of nine men; two other sections remained in cover.

It was flat, open country. We reached the north side of the bridge and climbed the railway embankment. We got there without any problems. That’s why I shouted to my men that we might as well move on immediately and take the entire bridge.

I looked back to see if they were following me. We threw a smoke grenade, but unfortunately the wind came from the wrong direction. Still, it did provide some coverage. We ran across the bridge as fast as we could through the smoke. He was very tall.

The surface consisted of metal plates on which our nailed boxes made a hellish noise. After about fifty meters we had to stop. I told them to take cover. We had just surfaced the water.

As we lay there, the middle span of the bridge flew into the air. The metal plates right in front of me rose. We were lucky we had just stopped, otherwise we would have all flown into the air. Now no one was injured in the explosion.

Immediately afterwards I felt something hit my leg. I asked if anyone had fired a shot, but they all shouted in unison that no. It had been a German bullet. Then I felt a bullet sear through my right upper arm. My arm seemed to have come loose. He spun around, the bone completely dislodged. There were only a few shots fired, but the shooter had picked me out as the leader and eliminated me cleanly.

If we had been allowed to land near there, we could have stormed over and taken possession of that bridge would have been a piece of cake. Over there. At that location. In the meadows between the railway bridge and Oosterbeek. That was where we should have landed. But if necessary they had to drop us off at the wrong place. Now they had been warned three hours in advance and were able to blow up the bridge.”

The blowing up of the railway bridge was the responsibility of a mobile platoon unit from the Bataillon Krafft, which guarded the southern side of the bridges and the ferry.