Even before all British troops had landed west of Wolfheze on Sunday, September 17, the troops of the German 9th and 10 SS Armored Divisions had already been alerted.

To immediately clear up a major misunderstanding: the two armored divisions stationed near Arnhem had almost no tanks and mechanical artillery. Combined, the two divisions only had five working tanks and Sturmgeschütze that they could deploy.

Almost all tanks that appeared in the front area near Arnhem from Monday, September 18, were tanks that had been sent to Arnhem by the German army leadership via so-called Blitztransporte after the landings.

On Sunday, September 17, there were hardly any German Panzers. But even without tanks, the striking power of the 9th and 10th Panzer Divisions was much greater than the British had estimated.

The 9th and 10th SS Armored Divisions had been quartered by the German High Command at Apeldoorn, Dieren, Zutphen and other places above Arnhem to be reequipped. A month earlier, the two divisions had been virtually destroyed by the British and Canadians at Falaise.

The presence of the two armored divisions was reported to the English by the resistance in the Netherlands, but they concluded that there could not be much threat from the remainder of the German divisions.

Soon after the airborne landings at Wolfheze it became apparent that the British army leadership had completely misjudged this. The two divisions together had approximately 7,000 soldiers with combat experience. In addition, the divisions had artillery, anti-aircraft guns, armored personnel carriers and some tanks.

General Wilhelm Bittrich, who was in charge of the II SS Armored Corps of which the divisions were part, immediately ordered the two divisions into action when he heard about the airborne landings.

Bittrich ordered the 10th SS Armored Division to defend the Nijmegen sector. The 9th SS Armored Division, led by General Harzer, had to deal with the British at Arnhem.

Bittrich sent this order to the 9th SS Division around 4 p.m.:

“The Harzer division group is gathering in the Velp area and is preparing in such a way that an attack can be made from Velp on the enemy landed west of Oosterbeek, who has the strength has about a brigade. An advanced command post must be set up in Velp.”

The strength of the British who had landed at Wolfheze was underestimated by the Germans at that time. It was more than half a division that had landed, and not just a brigade. The Germans’ incorrect assumption is understandable, as only the three battalions of the 1st Parachute Brigade advanced to Arnhem. The rest of the troops stayed behind to protect the landing areas.

General Harzer had planned to have a column of about 40 armored cars and other vehicles from the SS Panzer Aufklärungs Abteilung 9 advance to Oosterbeek to fight the British paratroopers. This battalion of approximately 500 men, led by Hauptsturmführer Gräbner, was at that time the strongest unit of the 9th SS Armored Division.

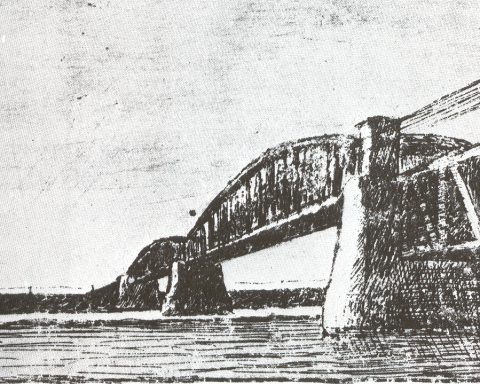

But around 4:30 p.m., General Harzer received a new order from headquarters, urging him to act urgently. “Fast action is required! The capture and preservation of the bridge in Arnhem are of decisive importance.”

In addition, SS Panzer Aufklärungs Abteilung 9 was ordered to drive across the Rhine Bridge to Nijmegen for reconnaissance to see whether any Allies had landed between Nijmegen and Arnhem. Thirty half-tracks and other cars took off with Gräbner in the lead around 5:30 p.m.

Harzer overlooked the last part of Bittrich’s order. It stated that Gräbner’s reconnaissance battalion also had the task of securing the Rhine bridge. About an hour after Gräbner and his battalion had driven over the bridge towards Nijmegen, the 2nd Battalion led by John Frost arrived at an almost undefended Rhine bridge. The bridge was defended by only a handful of men from the original guard detachment.

The order to send Gräbner with the bulk of the armored cars to Nijmegen meant that Harzer had only ten armored cars and other reconnaissance vehicles left for the battle at Oosterbeek. These vehicles were sent to the British via the Amsterdamseweg, where they encountered the British 1st Battalion led by Colonel Dobie near the Koude Herberg near Oosterbeek. Dobie then decided to try to reach Arnhem via the southern route.

Kampfgruppe Spindler

Several units of the 9th SS Armored Division that were stationed near Arnhem had rushed to Arnhem on their own after the airborne landings to defend the city. The most important German unit was the 9th SS Armored Regiment led by Sturbahnführer Spindler. In addition, the 120-man SS Pionier Bataillon 9 of Hauptsturmführer Möller had also arrived at the airborne landings.

After Spindler reported to General Harzer at the beginning of the evening on Sunday, September 17, that his troops were forming a defense line on the west side of Arnhem, Spindler was instructed by Harzer to establish a front along the main roads from the Rhine to the Amsterdamseweg. against the British. Moreover, from the track, this line had to extend from the northern edge of the track to Oosterbeek station and further north via the Dreyenseweg.

German troops near Spindler’s line were ordered by German headquarters to join ‘Kampfgruppe Spindler’.

Serious defense ring

The airborne landings at Wolfheze had completely taken the Germans by surprise. But because the Germans responded adequately and, above all, very quickly near Arnhem, they were quickly able to stop the advance of the British with impressive improvisation skills. Only six hours after the British airborne landings, there was already a serious defense ring on the west side of Arnhem.

Along the main access roads to the Arnhem Rhine Bridge, German soldiers were well dug in and had mortars, artillery and other heavy weapons at their disposal. Only John Frost’s 2nd Battalion managed to reach the Rhine Bridge along the Rhine at the beginning of the evening.

The Germans had no intention of allowing the rest of the British access to the city. For unknown reasons, both the 1st and 3rd British Battalions stopped in Oosterbeek for the night.

The Germans are not sitting still. The lack of action on the British side only gives them more time to strengthen their defense on the west side of Arnhem.