On Thursday morning at 4:30 am, General Urquhart had confirmed to headquarters that the Westerbouwing was in British hands and that the Driel ferry, with a mooring at the Westerbouwing, could be used later that day by the Poles to enter the British lines from Driel. to strengthen Oosterbeek.

Things, like almost everything during Operation Market Garden, turned out very differently.

After approximately 1,000 Polish paratroopers from the 1st Independent Polish Airborne Brigade landed near Driel around 5 p.m., a group of Poles was sent by General Sosabowski to the landing stage of the foot ferry to make contact with the British on the north side with light signals.

To their astonishment, shots were immediately fired at the Polish soldiers from the north side of the Rhine. Lieutenant Kaczmarek:

“We came under heavy fire from the other bank. We ran and took cover behind some piles of rocks. It was a miracle that no one was hit. We could hear the bullets ricocheting off the stones.”

General Sosabowski was furious when he heard about the events. After all, he had received a message shortly before departure that the ferry was in use. “How could that have happened in just a few hours?” he wondered.

Floated away ferry

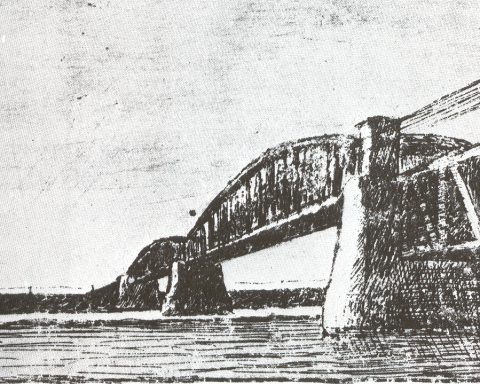

The British in Oosterbeek had been attacked from all sides that day. Due to a fierce German attack just before the Polish airborne, the British paratroopers had been driven from the Westerbouwing earlier that day. The Germans now had firm control of the northern jetty of the Drielse Veer.

The ferry itself was nowhere to be seen. Ferryman Peter Hensen had cut the cables after the German attack. In this way he wanted to prevent the ferry from falling into German hands. The ferry had drifted away with the current. It had been an act of resistance, but Hensen could not have known that his Drielse Veer was an essential link in the battle.

Because the foot ferry had drifted away, a planned British counter-attack to retake the Westerbouwing was canceled by Urquhart. The Poles had to find another way to get to the north side.

Had things turned out a little differently, the question remains how the Battle of Arnhem would have developed. With a serviceable foot ferry, 1,000 Poles had reinforced the British lines and many thousands of Allied troops probably followed in the days that followed. But the reality was that there was no ferry connection. The Poles had to improvise.

Rafts of trailers

The British tried to make contact by radio from Oosterbeek with the Poles on the south side of the Rhine, but this did not work. That evening, Polish captain Ludwik Zwolanski, who was serving as a liaison officer in Urquhart’s headquarters, swam across the Rhine to consult with the Poles.

Zwolanski indicated that the British would try to recapture the Westerbouwing and that the Royal Engineers would come to Driel with rafts from the north side of the Rhine. With these rafts the Poles could then be transferred to the British sector.

However, the British attack on the Westerbouwing came to nothing and the attempt by the Royal Engineers in Oosterbeek to build rafts from trailers did not really work either.

Sosbaowski had gathered a large part of his soldiers at the riverbank. But when he realized that there were no usable rafts, he ordered his men to withdraw to the river during the night of Thursday, September 21 to Friday, September 22. The Poles took up defensive positions around Driel.