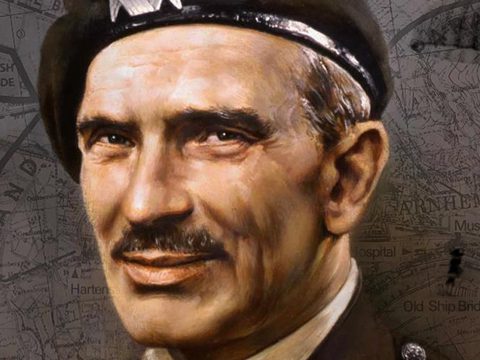

One of the last British officers to escape from captivity after the Battle of Arnhem is Scottish Colonel Graeme Warrack. Warrack headed the medical department of the British paratroopers in Oosterbeek. In February 1945 he managed to reach the Allied lines via the Biesbosch in the west of the Netherlansds with the help of Dutch resistance members.

The landing at Wolfheze on September 17, 1944 was not the first time for Colonel Graeme Warrack to take action during the war. Warrack had previously landed in Sicily during Operation Husky as a physician of the 1st Airborne Division and was involved in the fighting of British paratroopers in Italy.

Originally, Warrack was intended to lead the British medical corps from the hospitals in Arnhem during operation Market Garden. But it turned out differently. The British were pushed back into a perimeter in Oosterbeek and from the medical aid post in Hotel Schoonoord Warrack and his colleagues tried to take care of the flow of British wounded as good as possible.

Cease fire

On Sunday, September 24, after a week’s struggle, Warrack concluded it couldn’t go on like this. It was estimated that there were about 1,500 wounded within the British perimeter at the time, many of whom were in bad condition.

Warrack asked General Urquhart if he could agree a ceasefire with the Germans to remove the wounded. Coincidentally, German Major Egon Skalka, the head of the German medical corps, had also concluded that morning that something had to be done with the wounded in Oosterbeek.

Major Skalka had driven to the British bandage station in Schoonoord with a captured British jeep and a British prisoner of war who waved a red cross flag on the hood. At the bandage station he met Colonel Warrack.

Together the two doctors drove to the headquarters of the German general Bittrich in Arnhem. Bittrich gave Warrack and Skalka permission for a ceasefire. At 3 p.m. a two-hour ceasefire would start and some of the injured would be removed. The Germans promised to provide transport.

On his departure, Colonel Warrack received a bottle of brandy from Bittrich: “For your general.”

Indeed, that afternoon a ceasefire started at 3 p.m., which was respected by both parties. The Germans kept to their agreement and sent all ambulances, jeeps and other vehicles suitable for wounded transport to the British lines. In total, more than 450 injured soldiers were removed from the battle zone.

Apeldoorn

After the ceasefire, fighting continued for more than a day in Oosterbeek, before the British retreated over the Rhine. Graeme Warrack had decided to stay with the other British doctors to care for the injured.

As a prisoner of war, Warrack was transported together with the wounded by the Germans to Apeldoorn. The Germans had set up a barracks here as a hospital to care for the British wounded. Warrack was working here for weeks with British and German doctors. But by mid-October, most of the injured had been sent to prisoner of war camps in Germany. Warrack’s work was done. The Germans had already informed him that they were closing the hospital in the barracks within a few days.

Warrack decided that this was the time to go home. But how?

“I thought how awful it would be to be out in the open when it was raining and cold, without food, without a fire,” wrote Warrack after the war. “Suddenly I had a wonderful inspiration: why wouldn’t I hide inside the camp?”

Warrak discovered an empty space above the ceiling in a cupboard in his study. The room was big enough to hold out for a while. Warrack decorated the room with blankets, candles and a bucket that could serve as a latrine. Together with a large supply of food and drink, he hid in his “hidey hole”.

The Germans quickly realized that Warrack had disappeared. Warrack’s office was still under investigation, but Warrack was not found.

German roommate

Warrack was waiting for the barracks to be abandoned by the Germans. But that moment was delayed. After a week in his hiding place, Warrack’s room was given as a bedroom to a German soldier.

“He was sleeping restlessly, which meant that I didn’t get much rest myself either. My idea of secretly waiting for the English to arrive had apparently not been such a resounding thought,” said Warrack.

The next day, Warrack decided to sneak away anyway.

“I was terrified and expected to hear the cry ‘Halt’ at any moment, but nothing happened.”

Warrack ended up outside the barracks through a hole in the fence.

After a day of walking around outside, the British doctor decided to knock on the door of a Dutch house. Warrack was lucky. The people in Otterloo whom we had approached turned out to be active in the resistance. They had been involved in Operation Pegasus, where 130 stranded British soldiers escaped over the Rhine to the allied lines after the Battle of Arnhem.

With the help of the Dutch resistance, Warrack went into hiding with several people in the Netherlands for a few months. In February 1945 he was put over the river by the resistance after a cycling and walking tour in the dark via the Biesbosch and he reached the Allied lines.

Graeme Warrack wrote the book ‘Travel by dark’ in 1963 about his experiences during the Battle of Arnhem and about his escap.

The book was made into a film by the BBC in 1976 under the title: ‘Arnhem: story of an escape’.

Graeme Warrack was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his work as a doctor during the Battle of Arnhem and was awarded the honorary title ‘Honorary Physician to the Queen’ in 1958. Warrack died in 1985.