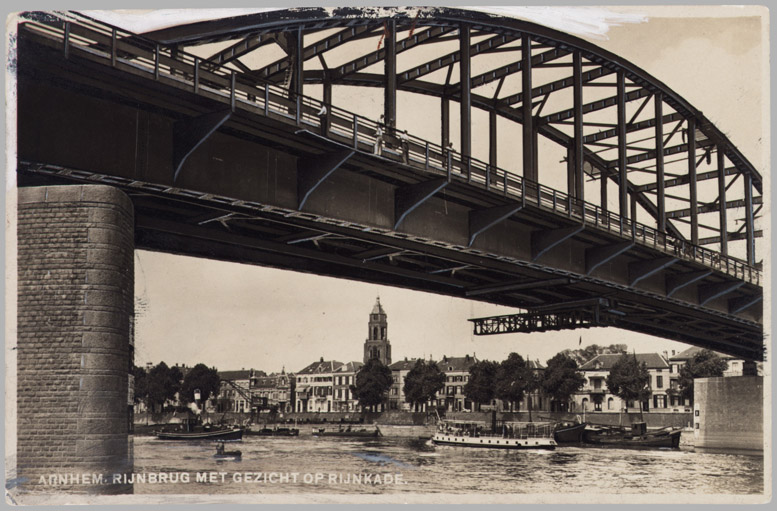

Around 8 p.m. on Sunday, September 17, 1944, the first British soldiers reached the Rhine Bridge near Arnhem. To their surprise, the British discovered that the bridge was not defended by German soldiers. In the confusion after the airborne landings, the German army leadership had forgotten to send soldiers to the Rhine Bridge.

After several military targets in Arnhem had already been bombed on the morning of Sunday, September 17, all German troops in the Arnhem area had already been put on high alert.

When the first British scouts landed at Wolfheze at 1:30 PM to occupy the landing areas, the Germans immediately sounded the alarm. All German troops in a wide circle around Arnhem were told that airborne landings were underway west of Arnhem. All German units in the region went into action.

The German army leadership soon figured out that the Rhine Bridge was the main objective of the British airborne landings. Many German units were therefore quickly transported to strategic locations around Arnhem to stop the advance of the British paratroopers.

The German response after the airborne landings was astonishingly fast and enormously effective. The vast majority of British troops never reached Arnhem. But the German army leadership did make a major blunder. In the confusion it was forgotten to also send German soldiers to the Rhine Bridge.

“The battle would probably have looked very different if a strong German unit had been immediately sent to the bridge in Arnhem,” said Heinz Harmel after the war. Harmel headed the 10th SS Panzer Division.

Waal Bridge

General Bittrich, who led the German defense, had sent a German unit across the Rhine Bridge. Because reports had been received at German headquarters that airborne landings had also taken place near Groesbeek, the strongest German unit present in the Arnhem region at that time was sent to Nijmegen.

The armored reconnaissance unit of SS-Hauptsturmführer Viktor Gräbner was ordered to check the area between Arnhem and Nijmegen for British troops with 30 armored cars. When they were not there, Gräbner had to leave some armored cars at the Waal Bridge to strengthen the German position there. In Bittrich’s eyes, Nijmegen was the Schwerrpunkt .

Gräbner’s armored cars drove south over the Rhine bridge around 6 p.m. That troop movement was seen by soldiers from the British 2nd paratroop battalion. The vanguard of the battalion under Colonel John Frost was at that time on the west side of Arnhem, in view of the bridge.

Two of the three British battalions that advanced to Arnhem after the airborne landings were stopped by the hastily formed German barrier line . Frost’s battalion’s predetermined route along the Rhine, however, was barely defended. Only at the railway viaduct at Oosterbeek and near the Elisabeth Gasthuis did firefights with German troops lead to delays.

Leaving the Rhine Bridge

After Viktor Gräbner’s column of armored vehicles had passed the Rhine Bridge, the Rhine Bridge looked like a deserted oasis. At that moment, the sound of firefights could be heard from the west side of Arnhem. There was fighting everywhere on the west side of Arnhem at that time. Fierce firefights took place between British and German soldiers on the Amsterdamseweg, in Heijenoord, on the Utrechtseweg and around the current Arnhems Buiten.

But it was suspiciously quiet on and around the Rhine Bridge. Dutch police officer Van Kuijck said after the war that he walked across the Rhine Bridge that evening around 7:30 p.m. and that he saw nothing or no one.

There were a few German soldiers at the Rhine Bridge at that time. These ‘bridge keepers’ had retreated to a small bunker on the north side of the bridge.

The first British units that reached the entrance to the Rhine Bridge via Eusebius Square around 8 p.m. were fired upon from the bunker. The British responded by firing a PIAT anti-tank weapon at the bunker. All Germans were probably killed. There were no more shots fired after that.

Colonel Frost established a defensive perimeter around the northern side of the Rhine Bridge. An attempt to capture the southern side of the bridge also failed. One of Gräbner’s armored cars had stopped on the southern ramp of the bridge after its reconnaissance tour between Arnhem and Nijmegen. The armored car’s machine gun was effective enough to keep the British at bay.

It took a while for the Germans to realize that at least some of the British had reached the Rhine Bridge. To their surprise, a German unit that was on its way from Deventer to Nijmegen by bicycle was suddenly fired upon north of the bridge in Arnhem.

“We were shot at from all sides,” said Rudolf Trapp, who was part of the German company of cyclists. “The British were entrenched in the houses. We couldn’t get them out of there.”

The German company eventually withdrew.

A German truck carrying 17 soldiers from an artillery unit was ordered to stop on the northern entrance to the Rhine Bridge in the evening by a British sergeant standing on the road.

German Lieutenant Joseph Enthammer: “Our unit of 120 men had received the order to drive to Emmerich at 7 p.m. We were delayed a bit, so our truck didn’t leave until 9 p.m. At the Rhine Bridge we were told to stop by the British.”

The Germans were taken prisoner of war.

Enthammer: “What could we have done? With the exception of a few guns we were unarmed. It came as a complete surprise that the Tommies had taken control of the Rhine Bridge.”

The German prisoners of war were lucky. Three other German trucks that subsequently tried to drive south via the Rhine bridge were unceremoniously attacked and set on fire.

After that it was clear to the Germans. The Rhine Bridge, the main objective of Operation Market Garden, was firmly in British hands. Viktor Gräbner discovered the next morning how strong the British position was, when he tried to break through the British defenses from the south with his armored cars. The entire unit was destroyed by John Frost’s forces.