To immediately clear up any misunderstanding. This story is about a pigeon. But the story of “William of Orange” is special and however far-fetched the facts may sound in this article: the story is completely true.

Radios

An important factor in the failure of the Battle of Arnhem stems from the fact that the British were equipped with the wrong radios.

The British paratroopers had been given the same radios they had used in North Africa two years earlier. In the barren, empty desert, the radios did fine. But in the built-up and wooded area of Arnhem, the radios had no range at all.

The problems that arose from this were unprecedented. Army units could not communicate with each other, nor could they report to the headquarters of General Urquhart’s division in Oosterbeek.

In turn, Urquhart was unable, during the early days of the Battle of Arnhem, to inform the British army command at Nijmegen or the commanders in London of the plight of his troops.

Reconnaissance flights

When no radio messages came in from Arnhem at the start of the Battle of Arnhem, the High Command in London concluded that there had to be something wrong with the radios.

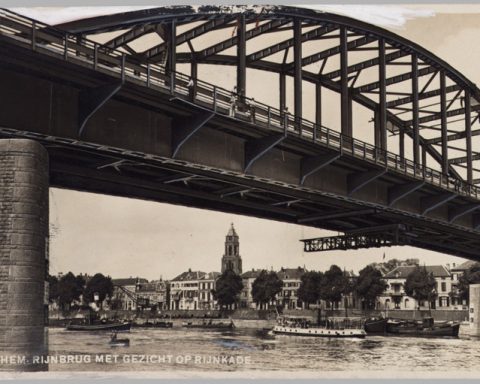

Photographs were made around Arnhem via reconnaissance flights by Spitfires. The famous photo of the destroyed German armored cars in the ramp of the Rhine Bridge was taken during one of these reconnaissance flights.

As a result, the British High Command generally knew that things were not going according to plan in Arnhem, but how bad the situation was at that time had not yet fully penetrated in London at that time.

Surrounded

That changed on Tuesday, September 19, 1944 by a message that arrived in London via a carrier pigeon. That pigeon was called William of Orange.

The pigeon was taken to Arnhem by the troops of John Frost, together with a number of his own kind. Surrounded by German troops and unable to contact Oosterbeek by radio, Frost decided to release a carrier pigeon.

William of Orange had a note on his leg saying that Frost’s troops occupied the northern ramp of the bridge, but that they were cut off from the rest of the British troops and urgently needed air support to continue the fight against the Germans.

William of Orange was released at 10:30 am and reached his loft in Cheshire in England at 2:55 pm.

“A distance of 400 kilometers in 4 hours and 25 minutes. An absolute record, ”Stewart Wardrop of the Royal Racing Pigeon Association told the Daily Mail .

“If you consider that he spent days in a cage for days and then was released under enemy fire and had to fly 200 kilometers over open water to reach England, that is quite an achievement.”

According to tradition, the release of the carrier pigeon was not without problems. While under enemy fire, a British paratrooper released the carrier pigeon under the ramp of the Rhine Bridge.

Instead of flying away, the pigeon sat nearby. Only after a British soldier fired a few shots at the pigeon with a stengun, did he fly up to England.

Award

Only after the message from the carrier pigeon did the British High Command realize that it was really wrong in Arnhem. However, it was of little use to John Frost. The weather conditions did not allow the requested air support to be given.

Incidentally, the British in Oosterbeek managed to get the radios to work on Tuesday 19 September and there was an (unreliable) connection with the allied headquarters at Groesbeek.

William of Orange was not the only carrier pigeon that John Frost’s troops had with them. More pigeons have been released, but William of Orange is the only one who has returned to England.

Dickin Medal

That performance was immediately valued by the British. William of Orange was awarded the Dickin Medal: the Victoria Cross for animals. William of Orange was the 21st animal to receive the award.

The award was created in 1943 by animal lover Mrs. M. E. Dickin, who previously founded the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals .

The award that William of Orange received was awarded a medal with the text ‘For Gallantry, We also serve’ .

After the war, William of Orange was bought by a pigeon fancier for the sum of 135 British pounds and lived for another ten years.